There are discoveries that arrive like thunder, and others that come as a faint glimmer in the dark. This one began far below the ocean’s surface, in waters so deep and still they resemble a second sky turned upside down. There, suspended in the Mediterranean abyss, delicate instruments waited patiently for a signal almost too subtle to imagine. When it came, it was only a single detection — but its implications may ripple across cosmology itself.

The particle in question was an ultra-high-energy neutrino, captured by the KM3NeT deep-sea observatory. Neutrinos are often called “ghost particles” because they pass through stars, planets, and even our own bodies with almost no interaction. Trillions flow through Earth every second unnoticed. Yet on rare occasions, one collides with matter and leaves behind a brief flash of light — a signature that sensitive detectors can record.

What makes this event remarkable is its energy. The detected neutrino carried an energy far beyond what human-made accelerators can achieve — orders of magnitude greater than the collisions produced at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider. Such immense energy suggests an origin in one of the universe’s most extreme environments: perhaps near a supermassive black hole, a violent gamma-ray burst, or another yet-unknown cosmic accelerator.

Current cosmological and astrophysical models attempt to explain how particles are propelled to such staggering speeds. They describe shockwaves around exploding stars, jets streaming from active galactic nuclei, and turbulent magnetic fields twisting through interstellar space. Yet a neutrino of this magnitude presses gently against those models, asking whether they fully account for what nature can produce.

In cosmology, energy is a clue to origin. If particles are arriving at Earth with energies that stretch or exceed expectations, scientists must reconsider either the engines that create them or the physics that governs their journey across billions of light-years. A single data point does not overturn theory. But it does open a question — and in science, a well-placed question can be transformative.

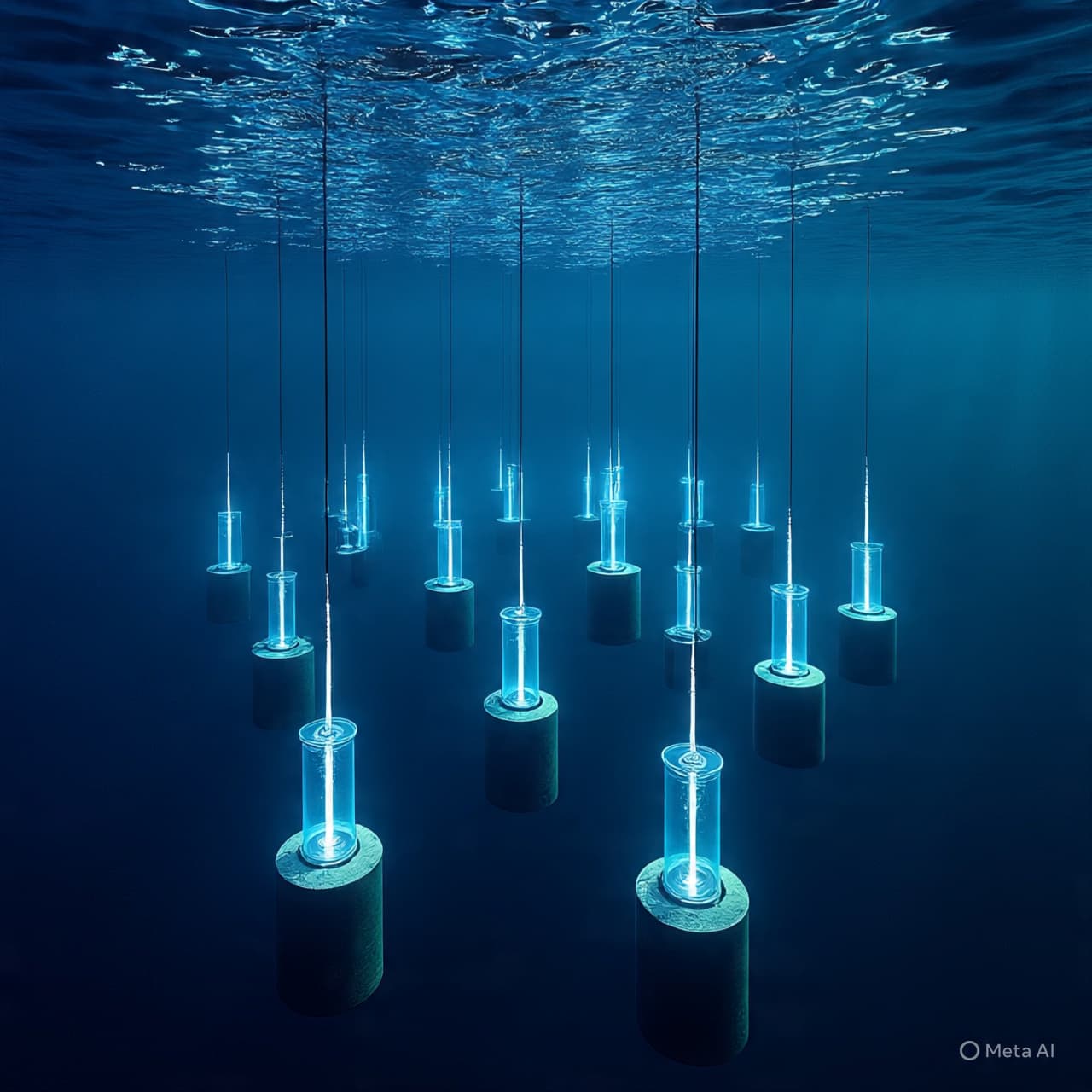

The deep sea plays an essential role in this quiet revolution. At depths exceeding three kilometers, darkness shields the detectors from background noise. When a neutrino interacts with water molecules, it creates a faint bluish flash known as Cherenkov radiation. Thousands of optical sensors, arranged like a submerged constellation, capture these flickers and reconstruct the particle’s path.

The beauty of this detection lies not in spectacle but in precision. It represents the growing maturity of neutrino astronomy — a field that complements traditional telescopes and gravitational wave observatories. Together, these tools form what scientists call “multi-messenger astronomy,” where light, particles, and spacetime ripples all contribute to a unified cosmic narrative.

Still, caution tempers excitement. One event cannot redraw cosmology alone. Researchers will need additional detections to determine whether this neutrino is an outlier or part of a broader population of ultra-energetic visitors. Patterns, not singularities, ultimately reshape theory. Yet every pattern begins somewhere.

In the measured cadence of science, this deep-sea signal is less a proclamation and more an invitation — to look deeper, to build larger detectors, to refine equations that describe the universe’s most violent processes. It reminds us that even in the quietest corners of Earth, we are listening to echoes from the farthest reaches of space.

The ocean floor, long associated with mysteries of our own planet, has become a bridge to the cosmos. And from that bridge came a single flash — small in duration, vast in implication — gently challenging us to rethink what powers the universe’s grandest accelerators.

AI Image Disclaimer Images in this article are AI-generated illustrations, meant for concept only.

Sources Nature ScienceAlert Scientific American The Guardian Reuters