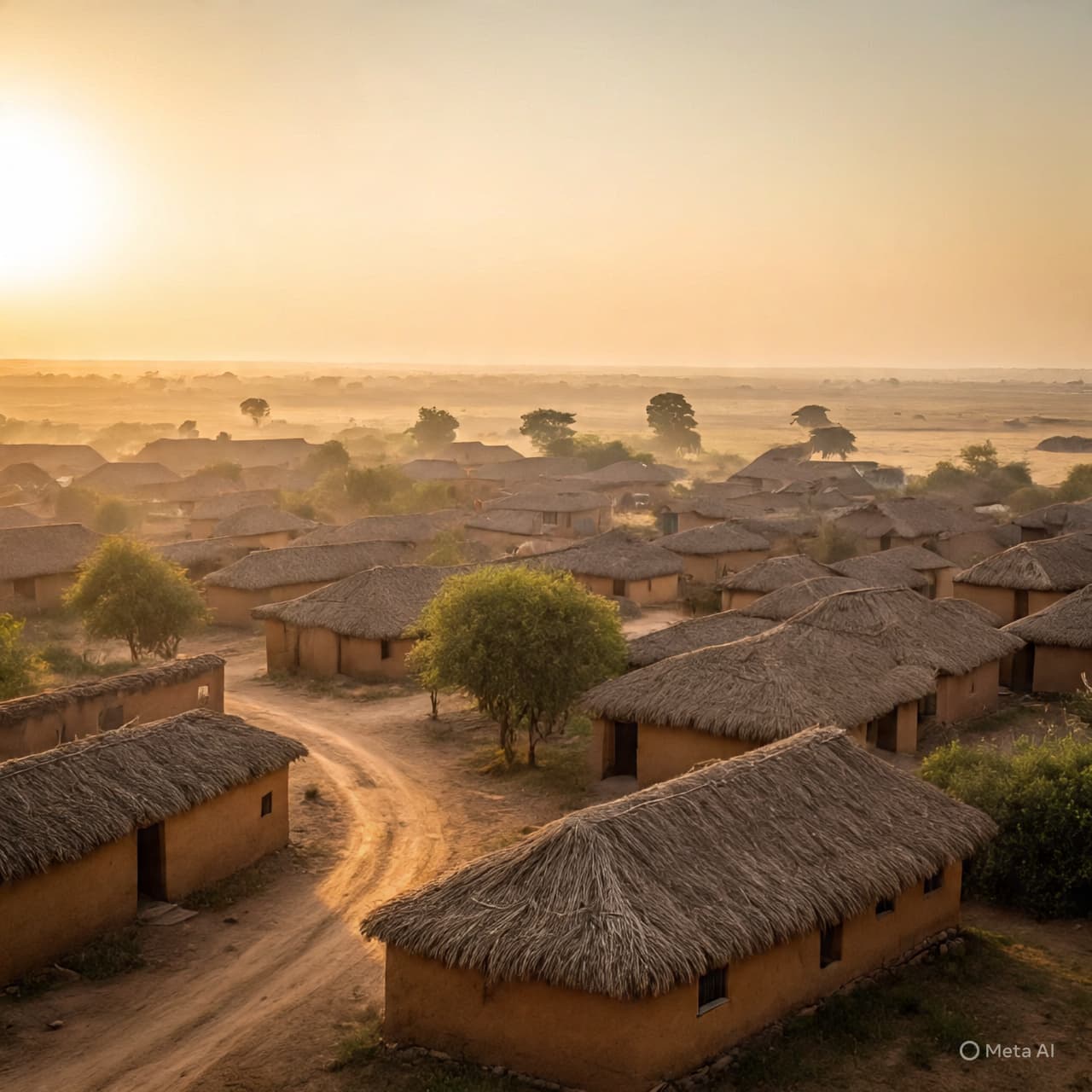

In the lowlands of Upper Nile, morning often arrives softly, drifting across grassland and river bends before the heat settles in. Villages wake slowly. Smoke rises from cooking fires. Footsteps trace the same paths they have followed for generations.

Yet even in places shaped by routine, news has a way of traveling faster than daylight.

South Sudan’s opposition group, the South Sudan People’s Defense Forces (SSPDF), said its fighters have captured the town of Motot after clashes with forces aligned to the Sudan People’s Liberation Army-In Opposition (SPLA-IO). The claim, delivered in measured language, adds another entry to a long ledger of contested ground in a country still learning how to live with fragile peace.

Motot sits in Upper Nile state, a region where rivers double as roads and loyalties have often shifted with the seasons. Control of such towns carries both practical and symbolic weight. It shapes who moves freely, who collects taxes, who provides security, and who speaks for the local population.

According to the SSPDF, fighting erupted between its forces and SPLA-IO units positioned near Motot, culminating in what the group described as a successful takeover of the area. The SPLA-IO has not publicly confirmed the loss, and independent verification remains difficult in a landscape where access is limited and communication unreliable.

What can be confirmed is the pattern.

South Sudan’s peace agreement, signed in 2018 and revitalized in subsequent years, was meant to draw a line under the civil war that killed hundreds of thousands and displaced millions. The deal brought rival leaders into a unity government and promised security sector reforms, unified armed forces, and national elections.

Progress has been uneven.

Clashes between rival factions still flare in parts of the country, often tied to local power struggles, unresolved command structures, and competition over territory. Each confrontation chips quietly at public confidence, even when leaders in Juba reaffirm their commitment to peace.

For communities near Motot, the meaning of a “capture” is less about statements and more about what changes on the ground. Which uniforms appear at checkpoints. Whether markets reopen. Whether families feel safe walking to water points or tending fields.

Humanitarian groups have repeatedly warned that insecurity in Upper Nile complicates aid delivery in an area already facing food shortages, flooding, and displacement. Any new fighting, even if brief, risks pushing vulnerable households closer to the edge.

The SSPDF framed its claim as part of defensive operations, accusing SPLA-IO forces of initiating hostilities. Such language is familiar. In South Sudan’s long conflict, nearly every clash is described as a response, rarely as an opening move.

Meanwhile, regional and international partners continue to urge restraint and dialogue, pressing all sides to respect the ceasefire and accelerate stalled reforms.

In Juba, political life carries on with formal meetings and public assurances. In towns like Motot, politics arrives in quieter ways — through rumors, distant gunfire, or the sudden appearance of new armed men on familiar streets.

By nightfall, the land looks unchanged. The river keeps moving. Stars settle into place. But beneath the calm surface, the question lingers, as it has for years: whether the country is slowly inching toward lasting stability, or merely circling within the same fragile patterns.

For now, Motot’s name joins a long list of places whose fate is spoken in claims and counterclaims — small dots on a large map, carrying the heavy hopes of people who want nothing more than ordinary days.

AI Image Disclaimer Visuals are AI-generated and serve as conceptual representations.

Sources Reuters Associated Press AFP Al Jazeera UN Mission in South Sudan