There are parts of our modern world that hum along quietly — the unseen infrastructure carrying the voices, music, and news that shape our days. Among these, radio and television transmitters perform a kind of invisible choreography: signals leaving one place, arriving somewhere else, connecting communities without fanfare. But in early February 2026, a cautionary note rippled through that quiet universe. Broadcast-gear manufacturer GatesAir issued a stark, almost poetic reminder to its customers: Never expose transmitters and their control systems to the public Internet. Suddenly, what was once routine technical guidance felt like a broader meditation on the fragility of connection in a digital age.

The advisory comes after a series of confirmed cyber-intrusions into broadcast equipment. In several reported cases, broadcasters found that remote access interfaces — left reachable on public IP addresses — were exploited by bad actors. In one unsettling incident, a station’s Radio Data System (RDS) display — the scrolling text many listeners see on digital radios — was commandeered to show offensive, racially charged messages. It was a moment that reminded an industry built on trust and public service just how vulnerable its backbone could be when it stands exposed like an open door.

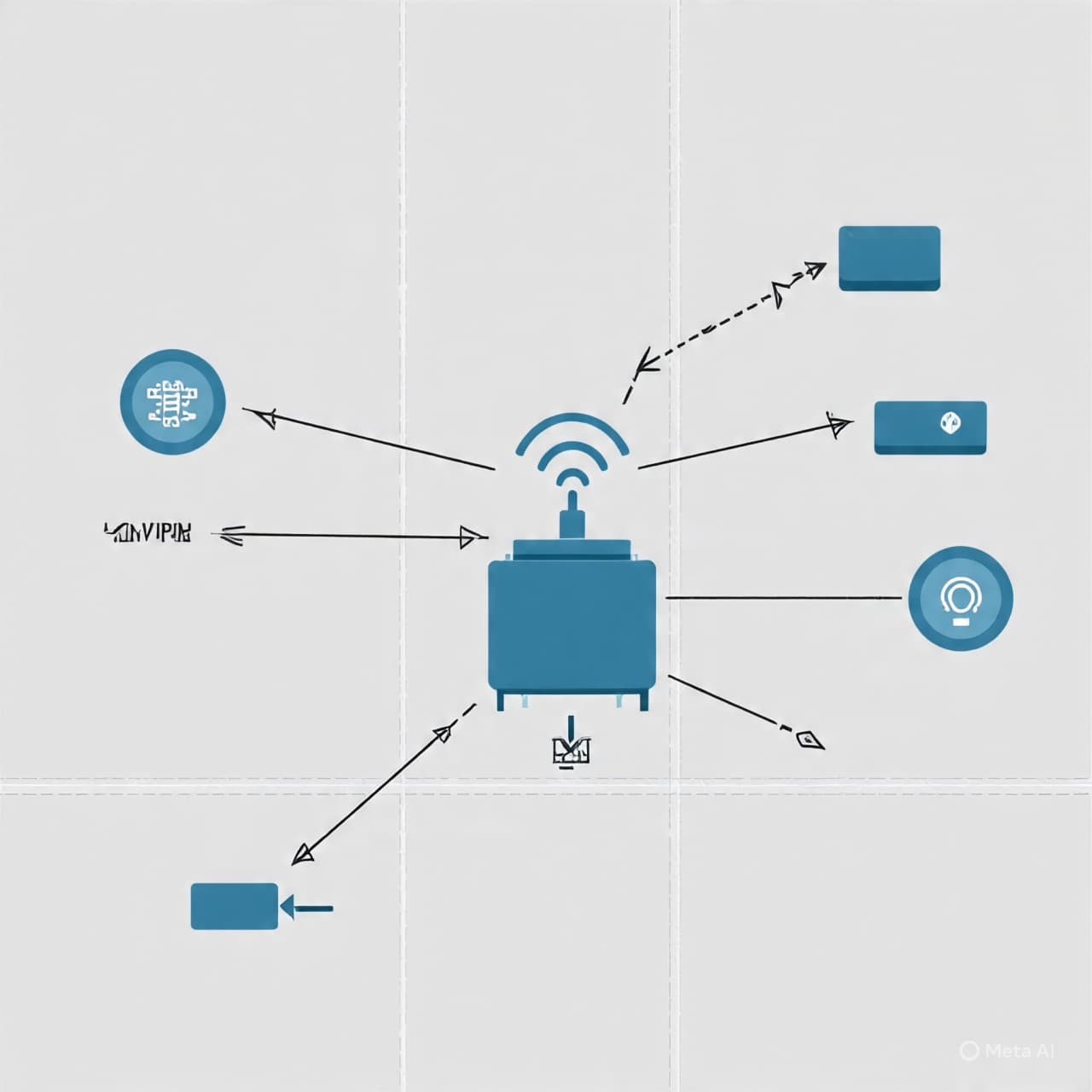

GatesAir’s directive is both simple and profound: don’t let transmitters sit on the public Internet without protective barriers. In practice, this means removing public IP addresses from critical control interfaces and placing such equipment behind layers of defense — virtual private networks (VPNs), firewalls configured to deny all but necessary traffic, segmented management networks, and isolated operations centers. These measures turn a direct line into a guarded gateway, inviting only trusted hands to interact with the gear.

This warning echoes larger conversations in the communications sector about the intersection of operational technology and cybersecurity. Once, broadcast transmitters were largely analog devices, isolated and benign. As these systems became networked for remote control and monitoring, they inherited all the risks of digital exposure. In recognizing this shift, GatesAir’s message was less about alarm and more about stewardship: the public airwaves deserve systems protected from the unseen threats that move through wires and wireless alike.

Government regulators have underscored similar themes. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has in recent years highlighted cybersecurity best practices for communications infrastructure, stressing multi-factor authentication, offline backups, staff training, and careful network segmentation to stave off ransomware and other exploits. Broadcasters, educators, and technical teams now find themselves balancing legacy equipment with modern network realities, where connection without protection can be an invitation to disruption.

For many in the field, the directive from GatesAir landed like a gentle but urgent nudge — a reminder that the signals filling the airwaves carry more than sound; they carry trust. And in a world where digital risks are as real as broadcast frequencies, that trust is strengthened not by exposure, but by careful and thoughtful protection.

AI Image Disclaimers (Rotated Wording) “Visuals are created with AI tools and are not real photographs.” “Illustrations were produced with AI and serve as conceptual depictions.” “Graphics are AI-generated and intended for representation, not reality.” 📚 Sources • Radio World industry report on GatesAir transmitter security guidance.